by Winston Rods | Aug 6, 2021

Our bamboo shop in Twin Bridges, MT is a modest place, but rich in tradition. Walking through the front door, one is greeted by a deep sense of history and a familiar hum of a workshop. We’re currently working on orders coming in from all over the world — from Hungary to New Zealand. One will notice quickly that bamboo is not dead.

The building process starts at sourcing and selection of the finest cane available. Bamboo, also, known as Arundinaria amabilis or “The Lovely Reed”, is a grass and not a type of wood. Our cane stocks come in 11 foot sections, sourced from the Sui River region in China.

As illustrated below, the bamboo culms are sorted based on node spacing. A node is a growth ring (solid joint). These growth rings occur at various lengths along the culm. Each culm of bamboo is unique. This is a large part of the reason why building bamboo rods is such an extensive process.

Unlike graphite, bamboo is not standardized in its density of power fibers. The grain, node spacing, wall thickness, and fiber density are unique to each culm, which is why they must be individually tailored to fit the specifications of the various rods and their individual sections.

Unlike graphite, bamboo is not standardized in its density of power fibers. The grain, node spacing, wall thickness, and fiber density are unique to each culm, which is why they must be individually tailored to fit the specifications of the various rods and their individual sections.

After the culms are cut to 5’ lengths, they are split into strips using a specialized splitting tool, as the photo below demonstrates. We will take these strips and begin the work of building a Winston bamboo fly rod. These split strips will make their first of many passes through the milling machine to be cleaned up. After milling, the strips are then heat cured to set the natural resins in the cane and impart a warm honey-colored look.

Once cured, the strips begin a long process of milling each one to its finished dimension. We then take six perfect strips, assemble them with alternating node spacing and prepare the assembled strips for gluing that cures for a minimum of 10 days.

Once the glued strips are cured, we remove the cross wraps, sand off the enamel and sand to finish, ensuring that the Winston tapers are held. If our measurements are incorrect, we will scrap and restart. Good enough is not acceptable here at Winston.

After the parts are milled and sanded, it’s time for the aesthetic finishes. The finished sections are fitted with ferrules. We then set our tip top, guides, and grip.

Each rod is hand inscribed with the rod model, length and line weight. And, if there are any custom requests to do so, we can inscribe a name or short phrase on the rod. Finally, the rod is cleaned and prepped for a final varnish which seals the cane in a UV protective, beautiful gloss finish. After applying the final varnish, we allow the rod to hang for two weeks to allow for complete cure and drying.

Each completed Winston Bamboo rod comes with two matching tips, German silver uplocking hardware on an elegant wood reel seat, a Winston logo embroidered rod bag, and a powder coated aluminum rod tube. The finished product is a handcrafted, truly unique rod and a beautiful tool for fly fishing. A fine work of art and the result speaks for itself.

by Winston Rods | Aug 5, 2021

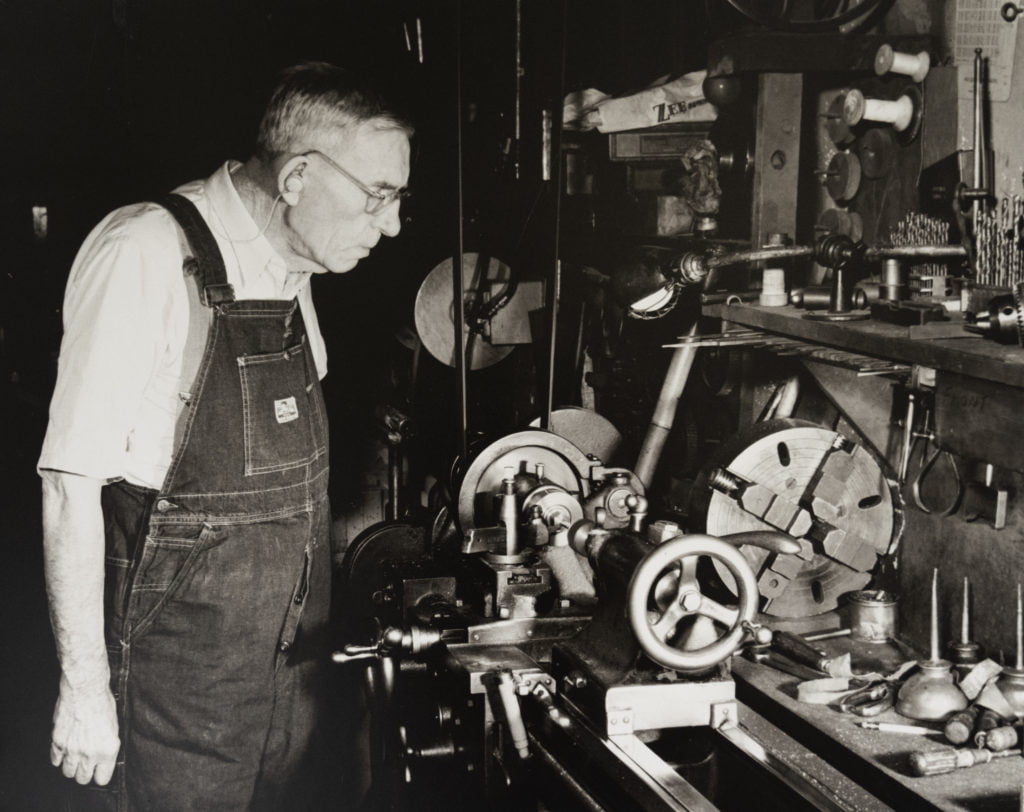

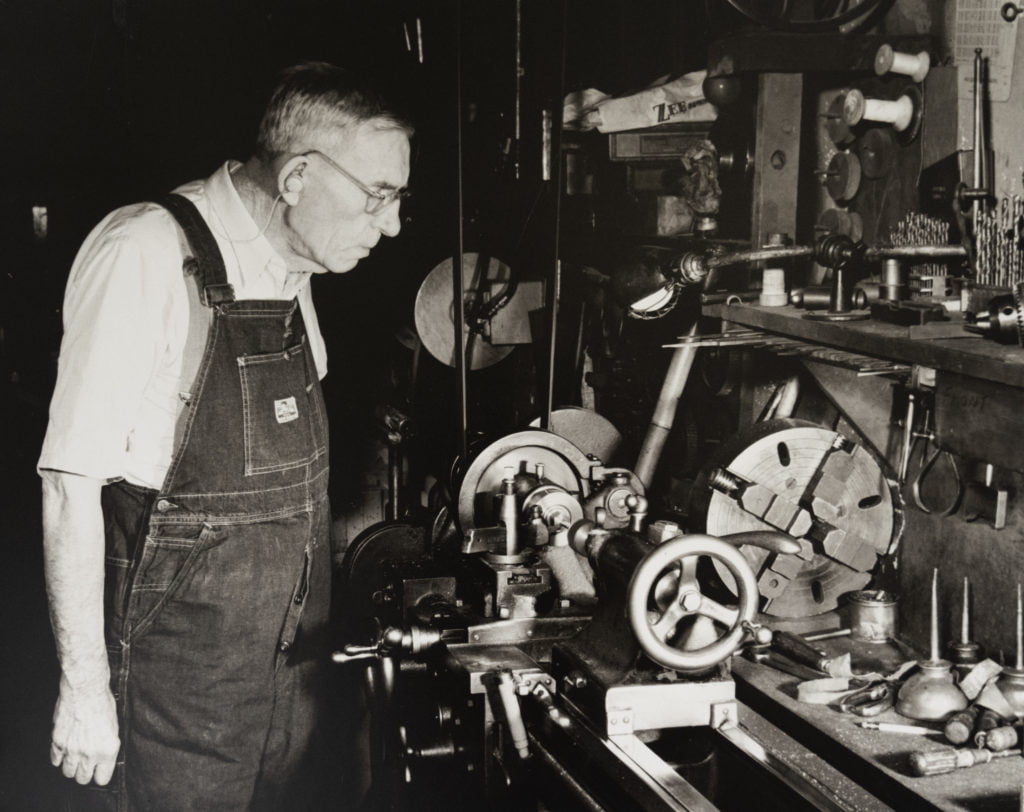

Following the stock market crash in 1929, a small company called the Western Fishing Rod Company was acquired by Robert Winther and Lew Stoner, and soon renamed the Winther-Stoner Manufacturing Company. The rods Winther and Stoner built were called “Winstons,” a contraction of the first letters of each of the men’s names.

Both Robert Winther and Lew Stoner were highly accomplished machinists. This enabled them to make almost all their metal components in-house, an important asset during the Great Depression. Stoner was also an inventor and developed Winston’s now famous hollow-fluted patented process. It didn’t take them long to establish their reputation as builders of outstanding bamboo rods.

During the late 1930s, tournament fly casting became popular in San Fransisco at the Golden Gate Angling and Casting Club. Casting tournaments became a catalyst in the evolution of bamboo rod design. The rules in force limited distance fly rods to a maximum weight of 5 ¾ ounces.

In 1934 Stoner developed the hollow-fluting design to develop a series of lightweight and powerful rods which went on to shatter all previous world distance casting records. In 1938, Winstonexpanded the hollow-fluting design to fly rods. These hollow-fluted rods were ideal for casting the heavy shooting lines used in the fly casting competition.

Ever Since, Winston’s bamboo tapers have been passed down through several generations of celebrated rod builders. Today, our passion and legacy for bamboo lives on with our current staff as we relish fishing cane every chance we get on our local rivers and beyond. Stay tuned for tomorrow, for our next post that details steps in building our famous bamboo rods.

by Winston Rods | May 5, 2021

By James Joiner

By James Joiner

Somewhere past the half-way mark of every Cape Cod winter the day comes where anglers collectively – often subconsciously – decree it time to return to more temperate habits. Rods and reels are assembled. Piles of flies crusted together under the guise of forgotten winter organizational projects get separated into trash and not. Waders are timidly tested in private to see if the past few month’s overindulgences caused any shrinkage. Group texts circulate as fairer-weather friends shake off social cobwebs and perform a loose headcount.

The snow is usually gone, ground sucking with mud, ice receded enough for returning osprey to find food. While Cape Cod is surrounded by ocean, it’s not salt water that rouses us from winter’s hibernatorial distractions. No, this is a time to look inward, toward the 996 ponds haphazardly scattered across our 90-mile man-made island. Left behind by the last ice age, these freshwater ‘kettle holes’ range in size from ‘damn, that’s a lot of water’ to “even ___ could cast across it” and, once the truck trout* arrive, they’re filled to the gills with ego-floatingly easy to catch stocked fish.

Growing up, we’d start checking freshwater beaches for the telltale tire tracks of tanker trucks backing in as soon as the sand stopped being hard enough to skateboard on. In modern times, the only legwork involved in figuring out when and where freshly delivered fish can be found is checking the state’s stocking report website, which gives up dates, locations, and fish type. I’m certain there are more adventurous souls who dislike such convenience, but personally I find it motivates me more than driving from pond to pond peering for signs of life. I prefer to save my audaciousness for bigger game, such as the striper migration’s arrival, only a month or two away at this point.

Notably naïve, stocked fish are easier prey than their more seasoned counterparts who wisely remain in deeper water while Powerbait and Woolie Buggers rain from the sky and thin the newly arrived herd. Growing up in a concrete tank with constant food and zero competition doesn’t do much to prepare these truck trout for Darwinian survival in the wild, a fact appreciated and taken advantage of by the army of local anglers, conventional and otherwise, who descend upon them. I like to imagine my own catch-and-release practice to be a crash course in pond-level street smarts, trading cheap thrills for sore lips and a life lesson in looking before you eat.

Regardless, it’s a great and time-honored way to get the casting arm back. It also helps keep my aging fingers nimble enough to tie knots while on the water, far more rewarding than doing so drunkenly in front of a Seinfeld marathon. Admittedly many of the bait fishermen, hidden behind their thick hedges of rods balanced on forked sticks and in PVC pipes, do bear an uncanny resemblance to certain eccentric cast members.

Even as barbless hooks train truck trout to survive in the wild, the admittedly easy hunt for them reignites an angling obsession that can be hard to maintain through New England’s long, dark, hermit-like winters. Sure, I keep up on blogs and magazines and, when I can, take a trip or two to try my luck in warmer climes. But truck trout are the pre-season training that get the mind and body ready for the rigors of striper season. Early mornings, late nights, missed meetings, estranged families – these become the norm as summer wears on through fall and single-mindedness drives us repeatedly to the sea in search of schoolies and larger. It’s a compulsion that will drive you crazy, though often just as you’re about to lose your last wit the season ends, the ocean once again grey, cold, and devoid of life until next year. Yeah, some of us drag it out long into the winter, but as weeks stretch into months without a sign of anything but frostbite the fire subsides and normal life returns, if only for a little while.

*Thanks @fish_fiends for the turn of phrase.

by Winston Rods | Nov 18, 2020

By Glenn K Chen

As a resident of the Great North since the early 2000’s, I’ve endured nearly two decades of long, dark, and frigid winters for those few brief months of fair-weather angling glory. From the onset of the midnight sun in late May through the fierce storms of October, anadromous salmonids are the focus of my annual pursuits in Alaska, and while I savor the opportunity to catch any species from the Pacific salmon clan, it’s the steelhead — among all members of the genus Oncorhynchus — that occupies a most special place in my angling soul.

As a resident of the Great North since the early 2000’s, I’ve endured nearly two decades of long, dark, and frigid winters for those few brief months of fair-weather angling glory. From the onset of the midnight sun in late May through the fierce storms of October, anadromous salmonids are the focus of my annual pursuits in Alaska, and while I savor the opportunity to catch any species from the Pacific salmon clan, it’s the steelhead — among all members of the genus Oncorhynchus — that occupies a most special place in my angling soul.

My fly fishing endeavors were hampered by a debilitating paralysis in my 20’s, which left me with very limited casting abilities using a single hand rod, and I thus angled for “steel fish” with conventional gear during most of the subsequent decades. While I did acquire a Spey outfit along the way, I really struggled with the unfamiliar setup — until I encountered a talented young guide named Trevor Covich. During one of my wilderness Alaska angling adventures, Trevor took me under his tutelage, and patiently helped me to learn the intricacies of both Spey casting and swing fishing. The two-handed rod has thus enabled me to overcome my physical handicap, and to enjoy once again pursuing my favorite species with tackle that I have not been able to use for many years.

The Winston two-handers are the ones I choose whenever I’m chasing Alaska steelhead. These rods have the ideal combination of flex needed to sense proper loading during the cast, followed by terrific power to send the fly to a distant holding lie on the forward stroke. (I also find their actions to be quite forgiving regarding casting faux pas, which is a blessing when my abilities decline after a long day’s effort.) Their outstanding durability is a really big plus as well, especially when you’re fishing in a remote spot where you’re limited with regards to the amount of gear you can bring — and where obtaining a replacement rod is nigh impossible.

Here on the Kenai Peninsula where I reside, the 11’ 6” Winston 6-weight rod is ideal for swing fishing steelies in our local, moderate-sized streams. For the larger and swifter rivers elsewhere in Alaska, I select the 13’ 3” models: rigged with Skagit heads and T8 or T11 sink tips, these longer rods enable me to effectively cover the myriad of angling conditions that are present in such systems.

This October, I was fortunate to once again venture to remote Alaska in pursuit of Oncorhynchus mykiss, and my Winston 13’ 3” 7-weight two-handers were again the rods I fished with on this weeklong adventure. As usual, we encountered both sunshine and light breezes, as well as driving rain with howling winds that nearly toppled me in the water — and these rods handled the adverse conditions with aplomb. Many of the steelhead fought with wild abandon, repeatedly leaping high and running far downstream, and really straining my tackle before surrendering reluctantly to a skillfully wielded net. The Winstons performed flawlessly during the entire trip, and accounted for dozens of out-sized steel fish (with stout girths) up to 35 inches in length

My final hookup resulted in my most memorable catch of the visit. I had just released a chrome-bright 32-inch hen that had jumped 12 times in succession during a lengthy fight that took me repeatedly into my reel’s backing. After releasing her, I continued to cast and wade down the underwater mid-river gravel bar, until I reached a spot where another step would submerge me too deeply. Making sure that my feet were firmly planted, I sent the fly towards the shoreline trees, and lowered the tip of my 13’ 3” Winston 7-weight as it began to swing. The savage strike occurred within seconds, nearly teetering me into the swift current as the unseen fish tore off downstream in a furious run. Fifty, then a hundred and then 200 yards of backing instantly disappeared, and I applied intense pressure in an attempt to halt this mad dash. For a few seconds, the steelhead held fast, angry head shakes telegraphed all the way up into the throbbing rod as it attempted to dislodge the offending hook – then the brief détente ceased, and my reel began screaming again as the remaining backing melted off the big Hardy Bougle.

As I was stranded in the middle of the river and thus unable to follow the fish, I yelled to our guide for assistance. Much to my relief, Garrett quickly arrived with the boat, and I tumbled in with less than 40 yards of backing remaining on the spool. We then chased the swiftly vanishing steelhead, steadily rewinding while keeping a deep bend in the rod, for seemingly endless minutes. When the running line eventually reached the tip top, we beached the boat – only to have my quarry tear off in more astonishing runs far downstream that took away much of my hard won effort.

As I was stranded in the middle of the river and thus unable to follow the fish, I yelled to our guide for assistance. Much to my relief, Garrett quickly arrived with the boat, and I tumbled in with less than 40 yards of backing remaining on the spool. We then chased the swiftly vanishing steelhead, steadily rewinding while keeping a deep bend in the rod, for seemingly endless minutes. When the running line eventually reached the tip top, we beached the boat – only to have my quarry tear off in more astonishing runs far downstream that took away much of my hard won effort.

This amazing steel fish wouldn’t give up, never rolling over as it dashed away repeatedly in spite of Garrett’s extra cautious attempts to approach it again and again with a landing net. He then decided that extreme stealth would be required to outwit the steelhead, so he crouched as low as possible, well below of me, and kept the net outstretched and motionless atop the substrate. After more tense and anxious moments, when the steelie would repeatedly veer away at the last second, I somehow managed to finally lead it gently into the waiting meshes – and whooped in sheer exultation when the 31-inch super hen was captured. Upon release, she immediately dashed away with amazing vigor, seemingly impervious to her lengthy struggle against modern angling technology. Truly, she was a supreme athlete among steelhead, and I hope that her indomitable genes will be forever passed on to future generations.

Glenn K Chen is a Winston enthusiast living in Alaska and enjoys all things two-hand.

by Winston Rods | Nov 13, 2020

November 2020

Twin Bridges, Montana

These beautiful new ultralight and soft technical hooded fishing shirts are designed to hang untucked with a generous fit. Made with 100% performance water-wicking 30+ UPF (Ultraviolet Protection Factor) polyester fabric, these shirts are our most recent edition to our TROUT TECH Conservation accessories and are perfect for a sunny day on the water!

(more…)

Unlike graphite, bamboo is not standardized in its density of power fibers. The grain, node spacing, wall thickness, and fiber density are unique to each culm, which is why they must be individually tailored to fit the specifications of the various rods and their individual sections.

Unlike graphite, bamboo is not standardized in its density of power fibers. The grain, node spacing, wall thickness, and fiber density are unique to each culm, which is why they must be individually tailored to fit the specifications of the various rods and their individual sections.

By

By

As I was stranded in the middle of the river and thus unable to follow the fish, I yelled to our guide for assistance. Much to my relief, Garrett quickly arrived with the boat, and I tumbled in with less than 40 yards of backing remaining on the spool. We then chased the swiftly vanishing steelhead, steadily rewinding while keeping a deep bend in the rod, for seemingly endless minutes. When the running line eventually reached the tip top, we beached the boat – only to have my quarry tear off in more astonishing runs far downstream that took away much of my hard won effort.

As I was stranded in the middle of the river and thus unable to follow the fish, I yelled to our guide for assistance. Much to my relief, Garrett quickly arrived with the boat, and I tumbled in with less than 40 yards of backing remaining on the spool. We then chased the swiftly vanishing steelhead, steadily rewinding while keeping a deep bend in the rod, for seemingly endless minutes. When the running line eventually reached the tip top, we beached the boat – only to have my quarry tear off in more astonishing runs far downstream that took away much of my hard won effort.